- Home

- Dani Shapiro

Devotion Page 13

Devotion Read online

Page 13

Be faithful to one’s husband; protect and invest family earnings.

Discharge responsibilities lovingly and conscientiously.

Accomplish faith.

Practice generosity.

Cultivate wisdom.

56.

Accomplish faith. There was a time in my life I would have scoffed at the notion, but now it seemed to me that faith really is an accomplishment. If accomplishment is, in part, defined as something requiring effort, certainly I was learning that faith required enormous effort.

My various rituals—the yoga, meditation, thinking, reading, Torah study—these were disciplines. They had become, to some degree, habit. But it was in the space around these rituals that faith resided. It was in the emptiness, the pause between actions, the stillness when one thing was finished but the next had not yet begun. Paradoxically, this was where effort came in, because it was so hard to be empty. To pause. To be still—not leaning forward, not falling back. Steady in the present—not even waiting. Just being. Could I just drive the car? Just cook dinner? Just walk the dogs in the front meadow and take in the rustling trees, the chirping critters in the distance? Why was it so difficult? So scary? Why did something that should be effortless require so much effort?

Every once in a while I would touch upon this state of emptiness. I would feel it for a second or two, perhaps three. And then I would quickly pull myself back, as if from an abyss. The Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield once asked an audience whether it’s possible to stop—let ourselves be a little emptier, a little more silent, more in touch with the spaces between words. The key word was between. When I allowed myself to fearlessly enter that between-place even for a few seconds, I accomplished faith.

57.

Life was very different in Connecticut. Though we were only a two-hour drive from the city, it might as well have been a five-hour flight. Friends occasionally came to visit, and I could practically see the thought bubbles escaping from their heads as they walked from their car to our front porch. Do they have neighbors? Does Jacob have anyone to play with? Where do they buy food? It wasn’t nearly as isolated as that, though in fact we didn’t know the people on our street. I saw them nearly every day through the windshield of my car, but this was the country, not the suburbs. No one greeted us with a homemade apple pie when we moved in. People tended to keep to themselves. I did have nicknames for my neighbors: the lady jogging; the couple walking; the one who doesn’t wave. In lieu of facts, I invented stories. The lady jogging was a recent widow who dealt with her grief by running; the couple walking was doing so on doctor’s orders for the sake of the husband’s health; the one who doesn’t wave was the grown daughter of a war criminal.

Jacob began preschool when we settled in, at a small school about fifteen minutes from our house. Each morning I drove past grazing cows, along a rutted dirt road, then pulled into the parking lot. I held Jacob’s hand as we walked through the glass doors into school, hugged him good-bye at his classroom door like every other parent in the place. Once he was settled in his classroom, I tried—this is the only word for it—I tried to escape.

Unlike many of the other moms, I didn’t want to hang out at Jacob’s school. I didn’t want to avail myself of the volunteering opportunities: the book fair, the auction. You couldn’t have paid me to stay for the Tuesday-morning Pilates class in the gymnasium downstairs. I was confused by my own response to the school community. Didn’t I want to be part of a community? Didn’t I love my child and want the best for him? Of course I did—so why was I making the quick dash back to my car, keeping my head down, avoiding eye contact? As I ducked past the other moms congregated in small groups, I felt isolated, though of course I was responsible for my own isolation.

Certainly I was still shivering in the shadow of Jacob’s illness. It was so rare, there were so few good outcomes—I had trouble trusting that it was really over. I had read stories on the Internet about relapses. I held my breath, waiting, girding myself, preparing for the worst, always thinking what if.

What if he has a seizure?

What if I let my guard down?

What if something goes wrong?

We had left New York, yes—but we had brought the past with us. Motherhood was still new for me—and I had barely known it without stomach-lurching fear. As I surreptitiously watched the moms, I envied their innocence. One of them told me that she had given birth to her youngest in the local hospital, and it was exactly like a hotel. “They bring you a smoothie afterward,” she said. But that hospital doesn’t even have a NICU, I thought. What if there had been an emergency?

I had begun to feel—and it was a bitter feeling—that the world could be divided into two kinds of people: those with an awareness of life’s inherent fragility and randomness, and those who believed they were exempt. Parenthood had created an even wider gulf between these two categories. I was firmly on the shore of fragility and randomness, and I could barely make out the exempt people dancing across the way. They seemed like a different species to me. Honestly, I resented them. They were having such a good time.

I didn’t know that there was a third way of being. Life was unpredictable, yes. A speeding car, a slip on the ice, a ringing phone, and suddenly everything changes forever. To deny that is to deny life—but to be consumed by it is also to deny life. The third way—inaccessible to me as I slunk down the halls—had to do with holding this paradox lightly in one’s own hands. To think: It is true, the speeding car, the slip on the ice, the ringing phone. It is true, and yet here I am listening to my boy sing as we walk down the corridor. Here I am giving him a hug. Here we are—together in this, our only moment.

58.

My mother’s mother—the only grandparent I ever really knew—spoke in Yiddish expressions that were variations on the same theme:

Alevei, she used to say whenever it seemed something really good might happen. This meant, It should only happen. It also somehow implied that it probably wouldn’t. Kayn ayn hora, she’d say. There should be no evil eye. It seemed the evil eye—a curse—was always in the process of being warded off, and the way to ward it off was to be aware of it. Plans were never made without a caveat. See you next week? God willing. You’ll come for Passover? I should live and be well.

As a child, I used to secretly make fun of my grandmother for all of her quaint expressions, but increasingly I found them creeping into my own vocabulary. God willing. The words themselves connote a God who’s actually keeping tabs on things—but maybe the meaning behind the words is this: the awareness, simply, of life’s unpredictability.

It was another Jewish grandmother, Sylvia Boorstein, who pointed out to me that these translated Yiddish phrases are in the hortatory subjunctive, an unusual tense that is used in the Buddhist metta phrases: May I be protected and safe; may I be contented and pleased. Not so different, really, from I should live and be well. The Old Testament also makes good use of the hortatory subjunctive: Let us come forward to the Holy of Holies with a true heart in full assurance of faith. These are statements that command oneself and one’s associates to join in some action—a communal urging.

I was back on my cushion, along with one hundred and fifty other people, once again listening to Sylvia. She was conducting a three-day silent retreat at the Garrison Institute, a former monastery perched on a cliff overlooking the Hudson River. I had signed up for the retreat impulsively, after seeing a notice about it on Sylvia’s Web site. I didn’t think too hard about what a silent retreat might mean. I figured it would be okay. Sylvia and I had become friends over the months since we’d first met at Kripalu. We’d read each other’s books, e-mailed back and forth, met for a long breakfast during one of her visits to New York from northern California. I felt a profound safety in her presence—the safety of being seen and known.

But here it was the first night of the retreat, and I was jittery. Would I be able to sleep in my little monk’s cell? The bed didn’t look very comfortable. What about the communal bathr

ooms? I hadn’t shared a bathroom with a group of strangers since college. Was there coffee in the morning? And what about the silence? No talking at all? Not good morning, hello, excuse me, thank you? What about texting? iChat? Was there Wi-Fi at the monastery?

“The mind ties itself into gratuitous knots, as a result of habit,” Sylvia was saying. Gratuitous knots were exactly what I was experiencing. One thought connecting to another, twisting around and around, becoming impossibly tangled. I looked at my tiny, gray-haired friend. She had been forty—and a mother of four—when she discovered Buddhism. Now, at seventy-three, she had a deep well of wisdom, compassion, and equanimity to draw from. I wasn’t much for auras, but I swear I could see her glow.

As we prepared to meditate on the navy blue zafus and zabutons laid out neatly in rows, I felt myself beginning to panic. I was reminded of the way Sylvia had described her own mind when she was first practicing: A mind with a lot of energy scanning the horizon for what to worry about. Who was I without my worry? How would it be—was it even possible?—to let go of the incessant fretting? I was so used to the noise in my head that I wasn’t sure if I even existed without it. Attempting daily meditation for twenty minutes in the privacy of my bedroom was one thing. Seventy-two hours of communal silence was quite another.

I closed my eyes. Sylvia was coteaching with the eminent Buddhist Sharon Salzberg, who had been Sylvia’s own teacher many years before. Sharon had gone to India in the early 1970s as a very young woman, and was one of a small core group responsible for bringing meditation to the West. Sharon gave us clear instruction: “Follow the breath in, follow it back out. If your mind wanders, bring it back.” My mind wandered almost instantly to the question of why that original core group of young American Buddhists consisted entirely of Jews. I ticked them off in my mind: Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, Stephen Levine, Sharon Salzberg, Mark Epstein—practically a minyan! Then I caught myself. My ankle throbbed. It was easier to think than to be.

Someone coughed. People shifted on their cushions. Creaking, sneezing, rustling, sniffling. There were endless distractions, inside and out. I thought of something Sharon had said earlier that evening: “The magic moment in the practice is the awareness that our attention has drifted and we’ve become distracted—and we begin again.” I must have come back to my breath dozens of times before the sound of the gong echoed throughout the hall. I was no different from our new puppy back home, who constantly lost track of his red ball, then looked around, sniffing the sky: Where’d it go? Oh, look over there! What a great twig!

It was nine o’clock—the end of the first session. One hundred and fifty of us shuffled to our feet. The woman in front of me bowed to the golden Buddha seated on his altar. People avoided eye contact. Down the hall and up the stairs we drifted—slowly, dreamily, deliberately. Doors opened and closed. The sound of running water. In the women’s bathroom, strangers brushed teeth side by side.

I walked into my room, changed into a robe and slippers. Everything around me felt foreign and unnerving. I reminded myself that I had willingly signed up for this. I was here to retreat into myself—to see the patterns emerging in my own mind. When Sylvia was my age, she regularly went on month-long retreats. She left her family, went to India. She arose each morning at four to meditate. Her wisdom had not been handed to her on a silver platter. What did I expect? Why should spiritual wakefulness be easy?

I climbed into my little bed and turned off the light. It was early. I was wide awake. Back home, Michael and Jacob were probably watching television. I wondered how Jacob’s day had been at school. And Michael was waiting for news about whether or not he had gotten a big screenwriting job. Maybe he had heard? Jacob’s school reading project was due on Monday. Would Michael remember to help him with it? How were the dogs? I felt selfish, I realized. Selfish and guilty for being away.

On the wooden desk a few feet from my bed, the green light on my computer glowed. Connect, connect! The pull of the outside world was irresistible. I turned on my iChat and saw that Michael was online. With a few magic keystrokes, my husband’s face filled my computer screen. He was sitting at his desk, in his office at home. I put on my earphones, so I wouldn’t disturb anyone. Even the sound of my fingers clicking against the keyboard seemed loud. He waved. I waved back.

Hi, I wrote.

“Hi,” he said. “Can you talk?”

No talking. Everything okay?

“The puppy drank out of the toilet and peed on the floor.”

Sorry. How’s Jacob?

“He’s good. I don’t know how we’re going to get this reading project done, though. It’s a logistical nightmare.”

Things fall apart when I go away.

“No, they don’t.”

They do. Things fall apart when I go away.

“No, honey. No, they really don’t.”

Maybe I should come home.

“Hi, Mommy!”

Jacob heard his father talking to me, and joined him on the screen. Even the dogs got in the picture. They were home, cozy and safe. I was so happy to see them—all of them. And at the same time, I remembered something Sylvia had said during her talk: “My ability to be present in the world with an open heart depends on my ability to be present to myself with an open heart.”

“Mommy, why aren’t you talking?”

I’m supposed to be silent, sweetie.

“That’s weird.”

Jacob was right. It was weird. I was writing to my family on a computer while they talked to me through headphones, in a tiny room in a former monastery on the Hudson River, where I had come to meditate. I was already cheating, sort of. But seeing them fill the screen had reminded me of what I was doing and why I was doing it.

Good night, guys.

“Love you, honey. Don’t worry about us. We’re fine.”

Love you too. See you Sunday, God willing. We should live and be well.

59.

Michael is seven years older than I am. He remembers hiding under his desk during duck-and-cover drills in elementary school; he remembers being in that same school when he heard the news that President Kennedy was shot. Michael’s a full-fledged baby boomer, and I’m on the cusp of Generation X. Along with the difference in our childhood memories, there is also this: he spent his teenage years doing hallucinogenic drugs, and I did not.

“So what was it like?”

We’ve had many conversations about tripping. Michael’s acid trips are, to me, a bit like the experiences he had as a foreign correspondent. He’s gone to places I’ve never been. Seen things I’ve never seen. And so I ask him—as if for a bulletin from the front of human consciousness.

“It’s like seeing at a deeper level,” he says. “You see more of what’s there. More of what makes everything up.”

“Like what?”

“Like…I don’t know…colors. Things moving. Molecules binding together. The pattern behind things.” Here he stops, self-conscious.

“And what about after you stop tripping? That pattern—do you feel like what you saw was real?”

“Oh, absolutely. You have no doubt that what you saw was real.”

60.

By the second day at Garrison, I felt intimately acquainted with my fellow sojourners, though we hadn’t exchanged a single word. We sat, then walked. Sat, then walked. We stood quietly in line for our meals, helped ourselves to tofu stir-fry, brown rice, beet salad. In the absence of human voices, other sounds were magnified: shuffling footsteps, the creak of a floorboard, the clang of silverware. At long tables, we dined next to one another, chewing in silence. The silence itself was a physical presence: a dense, soft blanket that hovered, floating over the dark turrets of the former monastery.

Some people gazed out the high windows at the dull winter sky. Others clasped their hands and bowed their heads in prayer. Still others looked around openly—I was one of these—and gave a small smile and a nod if they caught another person’s eye. We might have had very little in common in t

he outside world, but each of us had chosen these days to retreat, and that choice bound us. We were passengers on the same ship, together in the middle of the ocean.

Sights and sounds grew more intense. As in a sharply rendered pencil drawing, the outlines of my fellow retreatants were stark. A woman with short black hair paced the halls, her face a rictus of apprehension. A bearded man in a baseball cap sat on a bench, holding his head in his hands. A girl—she could have been no more than twenty—dreamily wrote in a notebook decorated with om stickers.

After each meal, we wandered slowly back into the meditation hall. People had staked out the prime real estate, leaving a scarf, a pair of glasses, a folded blanket, on a favorite cushion so that they could return to the same spot. In the back row of zafus—with easy access to the door—I left my notebook and pen. The notebook was one I had used, off and on, for a year. It was one of my favorites—writers are nothing if not fetishistic about our notebooks—and I brought it to Garrison with me because it had a few blank pages left.

Sharon and Sylvia took their places in front of the gold Buddha, then waited, looking out over the vast hall as people began to settle back onto their zafus. Stretching, coughing, fidgeting. So hard to be still, even in the silence. Especially in the silence. Sylvia adjusted her microphone.

“It’s the human dilemma,” she began. “Time and the body. It’s true that change is always happening.”

Change is always happening. So simple. So obvious, really—and at the same time so terrifying. A friend had recently sent me directions to her house, and in describing the way the names of the roads changed for no apparent reason, she had written: Everything turns into something else. No wonder I didn’t want to think about this. What was the point of thinking about this? Love, joy, happiness—all fleeting. Trying to hold on to them was like grasping at running water.

Inheritance

Inheritance Devotion

Devotion Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life

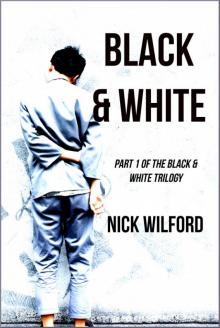

Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life Black & White

Black & White Slow Motion

Slow Motion Hourglass

Hourglass