- Home

- Dani Shapiro

Inheritance

Inheritance Read online

ALSO BY DANI SHAPIRO

Hourglass

Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life

Devotion: A Memoir

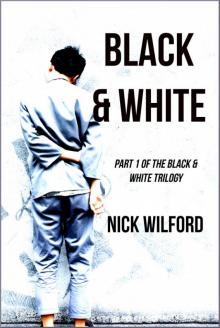

Black & White

Family History: A Novel

Slow Motion: A True Story

Picturing the Wreck

Fugitive Blue

Playing with Fire

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2019 by Dani Shapiro

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shapiro, Dani, author.

Title: Inheritance : a memoir of genealogy, paternity, and love / Dani Shapiro.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018024082 (print) | LCCN 2018050939 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524732721 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524732714 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Shapiro, Dani. | Women novelists, American—Biography. | Novelists, American—20th century—Biography. | Jewish women—United States—Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Cultural Heritage. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs.

Classification: LCC PS3569.H3387 (ebook) | LCC PS3569.H3387 Z46 2019 (print) | DDC 818/.5403 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018024082

Ebook ISBN 9781524732721

Cover photograph by Diana Weymar

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

v5.4

ep

Contents

Cover

Also by Dani Shapiro

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Epigraph

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part Two

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Part Three

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Part Four

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Acknowledgments

A Note About the Author

Reading Group Guide

This book is for my father.

Author’s Note

This is a work of nonfiction. In some cases, names and identifying details have been changed in order to respect and protect the privacy of others, and to keep a promise I made from the very start.

I shall never get you put together entirely,

Pieced, glued, and properly jointed.

—Sylvia Plath, “The Colossus”

If you want to keep a secret, you must also hide it from yourself.

—George Orwell, 1984

Part One

1

When I was a girl I would sneak down the hall late at night once my parents were asleep. I would lock myself in the bathroom, climb onto the Formica counter, and get as close as possible to the mirror until I was nose to nose with my own reflection. This wasn’t an exercise in the simple self-absorption of childhood. The stakes felt high. Who knows how long I kneeled there, staring into my own eyes. I was looking for something I couldn’t possibly have articulated—but I always knew it when I saw it. If I waited long enough, my face would begin to morph. I was eight, ten, thirteen. Cheeks, eyes, chin, and forehead—my features softened and shape-shifted until finally I was able to see another face, a different face, what seemed to me a truer face just beneath my own.

* * *

—

Now it is early morning and I’m in a small hotel bathroom three thousand miles from home. I’m fifty-four years old, and it’s a long time since I was that girl. But here I am again, staring and staring at my reflection. A stranger stares back at me.

The coordinates: I’m in San Francisco—Japantown, to be precise—just off a long flight. The facts: I’m a woman, a wife, a mother, a writer, a teacher. I’m a daughter. I blink. The stranger in the mirror blinks too. A daughter. Over the course of a single day and night, the familiar has vanished. Familiar: belonging to a family. On the other side of the thin wall I hear my husband crack open a newspaper. The floor seems to sway. Or perhaps it’s my body trembling. I don’t know what a nervous breakdown would feel like, but I wonder if I’m having one. I trace my fingers across the planes of my cheekbones, down my neck, across my clavicle, as if to be certain I still exist. I’m hit by a wave of dizziness and grip the bathroom counter. In the weeks and months to come, I will become well acquainted with this sensation. It will come over me on street corners and curbs, in airports, train stations. I’ll take it as a sign to slow down. Take a breath. Feel the fact of my own body. You’re still you, I tell myself, again and again and again.

2

Twenty-four hours earlier, I was in my home office trying to get organized for a trip to the West Coast when I heard Michael’s feet pounding up the stairs. It was ten-thirty in the evening, and we had to leave before dawn to get to the Hartford airport for an early flight. I had made a packing list. I’m a list maker, and there were a million things to do. Bras. Panties. Jeans skirt. Striped top. Sweater/jacket? (Check weather in SF.) I was good at reading the sound of my husband’s footsteps. These sounded urgent, though I couldn’t tell whether they were good urgent or bad urgent. Whatever it was, we didn’t have time for it. Skin stuff. Brush/comb. Headphones. He burst through my office door, open laptop in hand.

“Susie sent her results,” he said.

Susie was my much-older half sister, my father’s daughter from an early marriage. We weren’t close, and hadn’t spoken in a couple of years, but I had recently written to ask if she had ever done genetic testing. It was t

he kind of thing I had never even considered, but I had recalled Susie once mentioning that she wanted to know if she was at risk for any hereditary diseases. A New York City psychoanalyst, she had always been on the cutting edge of all things medical. My email had reached her at the TED conference in Banff. She had written back right away that she had indeed done genetic testing and would look to see if she had her results with her on her computer.

Our father had died in a car accident many years earlier, when I was twenty-three, and Susie thirty-eight. Through him, we were part of a large Orthodox Jewish clan. It was a family history I was proud of and I loved. Our grandfather had been a founder of Lincoln Square Synagogue, one of the country’s most respected Orthodox institutions. Our uncle had been president of the Orthodox Union. Our grandparents had been pillars of the observant Jewish community both in America and in Israel. Though as a grown woman I was not remotely religious, I had a powerful, nearly romantic sense of my family and its past.

* * *

—

The previous winter, Michael had become curious about his own origins. He knew far less about the generations preceding him than I did about mine. His mother had Alzheimer’s and recently had fallen and broken her hip. The combination of her injury and memory loss had precipitated a steep and rapid decline. His father was frail but mentally sharp. Michael’s sudden interest in genealogy was surprising to me, but I understood it. He was hoping to learn more about his ancestral roots while his dad was still around. Perhaps he’d even enlarge his sense of family by connecting to third or fourth cousins.

Do you want to do it too? he might have asked. I’m sending away for a kit. It’s only like a hundred bucks. Though I no longer remember the exact moment, it is in fact the small, the undramatic, the banal—the yeah, sure that could just as easily have been a shrug and a no thanks.

The kits arrived and sat on our kitchen counter for days, perhaps weeks, unopened. They became part of the scenery, like the books and magazines that pile up until we cart them off to our local library. We made coffee in the mornings, poured juice, scrambled eggs. We ate dinner at the kitchen table. We fed the dog, wrote notes and grocery shopping lists on the blackboard. We sorted mail, took out the recycling. All the while the kits remained sealed in their green and white boxes decorated with a whimsical line drawing of a three-leaf clover. ANCESTRY: THE DNA TEST THAT TELLS A MORE COMPLETE STORY OF YOU.

Finally one night, Michael opened the two packages and handed me a small plastic vial.

“Spit,” he said.

I felt vaguely ridiculous and undignified as I bent over the vial. Why was I even doing this? I idly wondered if my results would be affected by the lamb chops I had just eaten, or the glass of wine, or residue from my lipstick. Once I had reached the line demarking the proper amount of saliva, I went back to clearing the dinner dishes. Michael wrapped a label around each of our vials and placed them in the packaging sent by Ancestry.com.

Two months passed, and I gave little thought to my DNA test. I was deep into revisions of my new book. Our son had just begun looking at colleges. Michael was working on a film project. I had all but forgotten about it until one day an email containing my results appeared. We were puzzled by some of the findings. I say puzzled—a gentle word—because this is how it felt to me. According to Ancestry, my DNA was 52 percent Eastern European Ashkenazi. The rest was a smattering of French, Irish, English, and German. Odd, but I had nothing to compare it with. I wasn’t disturbed. I wasn’t confused, even though that percentage seemed very low considering that all my ancestors were Jews from Eastern Europe. I put the results aside and figured there must be a reasonable explanation tied up in migrations and conflicts many generations before me. Such was my certainty that I knew exactly where I came from.

* * *

—

In a cabinet beneath our television, I keep several copies of a documentary about prewar shtetl life in Poland, called Image Before My Eyes. The film includes archival footage taken by my grandfather during a 1931 visit to Horodok, the family village. By then the owner of a successful fabric mill, he brought my great-grandfather with him. The film is all the more powerful for the present-day viewer’s knowledge of what will soon befall the men with their double beards, the women in modest black, the children crowding the American visitors. Someone—my grandfather?—holds the shaky camera as the doomed villagers dance around him in a widening circle. Then we cut to a quieter moment: in grainy black and white, my grandfather and great-grandfather pray at the grave of my great-great-grandfather. I can almost make out the cadence of their voices—voices I have never heard but that are the music of my bones—as they recite the Mourner’s Kaddish. My grandfather wipes tears from his eyes.

In the year before my son’s bar mitzvah, I played him that part of the documentary. Do you see? I paused on the image of the rough old stone carved in Hebrew. This is where we come from. That’s the spot where your great-great-great-grandfather is buried. It felt urgently important to me, to make Jacob aware of his ancestral lineage, the patch of earth from which he sprang, the source of a spirit passed down, a connection. Of course, that tombstone would have been plowed under just a few years later. But in that moment—my people captured for all time—I was linking them to my own boy, and him to them. He hadn’t known my father, but at least I was able to give Jacob something formative that I myself had grown up with: a sense of grounding in coming from this family. He is the only child of an only child, but this—this was a vast and abundant part of his heritage that could never be taken away from him. We watched as the men on the screen swayed back and forth in a familiar rhythm, a dance I have known all my life.

* * *

—

So that 52 percent breakdown was just kind of weird, that’s all, as bland and innocuous as those sealed green and white boxes had been. I thought I’d clear it up by comparing my DNA results with Susie’s. Now, on the eve of our trip to the West Coast, Michael was sitting next to me on the small, tapestry-covered chaise in the corner of my office. I felt his leg pressed against mine as, side by side, we looked down at his laptop screen. Later he will tell me he already knew what I couldn’t allow myself even to begin to consider. On the wall directly behind us hung a black-and-white portrait of my paternal grandmother, her hair parted in the center, pulled back tightly, her gaze direct and serene.

Comparing Kit M440247 and A765211:

Largest segment = 14.9 cM

Total of segments > 7cM = 29.6 cM

Estimated number of generations to MRCA = 4.5

653629 SNP’s used for this comparison

Comparison took 0.04538 seconds.

“What does it mean?” My voice sounded strange to my own ears.

“You’re not sisters.”

“Not half sisters?”

“No kind of sisters.”

“How do you know?”

Michael traced the line estimating the number of generations to our most recent common ancestor.

“Here.”

The numbers, symbols, unfamiliar terms on the screen were a language I didn’t understand. It had taken 0.04538 seconds—a fraction of a second—to upend my life. There would now forever be a before. The innocence of a packing list. The preparation for a simple trip. The portrait of my grandmother in its gilded frame. My mind began to spin with calculations. If Susie was not my half sister—no kind of sister—it could mean only one of two things: either my father was not her father or my father was not my father.

3

A sepia photograph of my father as a little boy hangs just outside our living room, where I pass it dozens of times a day. He poses in a herringbone coat and bowler hat, white kneesocks and shoes, playfully holding a cane. His eyes are round, his smile impish. He was the oldest son born into a family obsessed with recording itself—a family conscious of its own legacy. Grandparents, great-uncles, great-aunts,

even distant cousins from the old country are scattered throughout my house. But it is the portrait of my father that is my favorite. Who is that? friends will ask. My dad, I will answer. He has been dead more than half my life and still the feeling is the same: a warm, quiet pride, a sense of connection, of tethering, of belonging.

The portraits and sepia photographs can be traced to the Eastern Europe of my forebears. My ninety-three-year-old aunt Shirley—my father’s younger sister—has been the family archivist. Years ago, she entrusted Michael and me with the task of digitizing the contents of a massive leather-bound family album. Jagged-edged photographs traced an evolution from the dusty shtetl to prosperous turn-of-the-century America. Michael took each one from the album and created an online version to share with the grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great-grandchildren, now numbering in the hundreds. There’s Grammy and Grampy about to set sail for Europe. My grandparents were regal and glamorous next to a trolley piled high with their steamer trunks. There’s Rabbi Soloveitchik and Uncle Moe with Lyndon Johnson. There’s Moe with John Kennedy. Men in yarmulkes next to presidents, their faces proud and lit with purpose.

Inheritance

Inheritance Devotion

Devotion Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life

Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life Black & White

Black & White Slow Motion

Slow Motion Hourglass

Hourglass